Modest Reductions in Interconnection Queues Do Not Mean Reform Has Achieved its Aims

In August, Lawrence Berkely National Lab released new data for its annual “Queued Up” report series, which compiles interconnection queue data from nearly all of the grid operators and utilities charged with managing America’s electric grid. Previous editions in the report series have greatly improved our understanding of the severe challenges facing our country’s electricity interconnection system, and this edition is no different.

For the first time in decades, the number of electricity projects in the interconnection queue—the line of electricity projects awaiting connection to the grid—shrunk. For many, this news might seem like evidence that interconnection reforms set in motion by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 2024 are having an impact. In reality, the landscape is much more complicated and not necessarily good news for clean energy growth.

Interconnection Bottlenecks Create Need for Urgent Reform

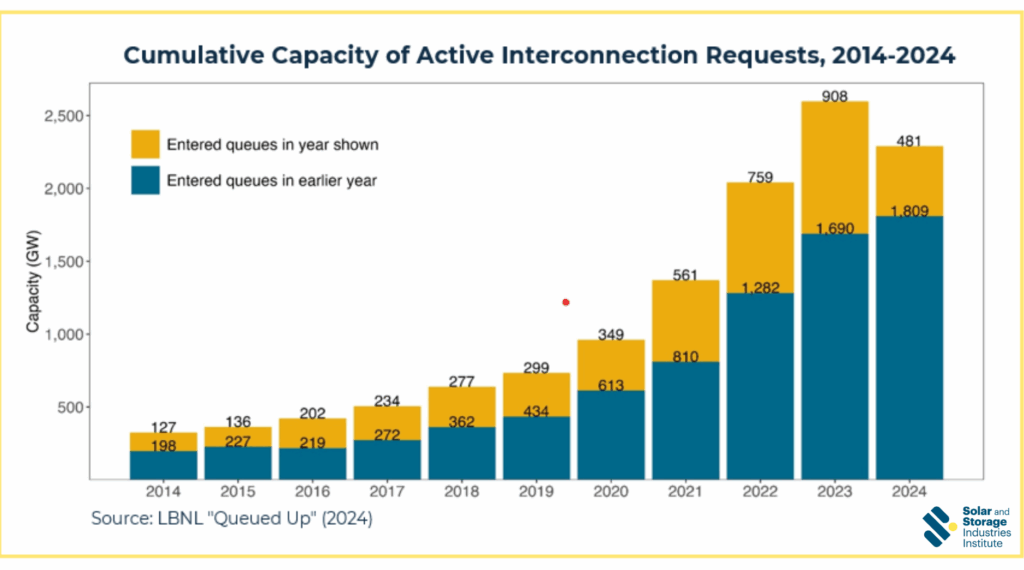

For years, the nation’s interconnection queue has grown unabated, driven by the explosive growth of renewable energy projects and an archaic interconnection process designed to serve a fossil-based grid. This combination of factors has led to record queue sizes that are nearly double the size of the existing generator fleet and with record wait times, with projects installed in 2024 taking nearly five years to complete the interconnection process.

The inefficiency of existing interconnection rules imposes costs on the entire electric system. The cost to interconnect a project has risen by 88% over the last decade—costs that are ultimately passed onto the consumer. Meanwhile, the existing system has led to reduced investment in the grid upgrades desperately needed to serve rapidly increasing electricity demand from AI, beneficial electrification, manufacturing and climate change.

In the summer of 2023, FERC issued Order 2023, which reforms the interconnection process by requiring streamlined review of interconnection applications and increasing the “project readiness” threshold for projects seeking to interconnect. While the order addresses some of the issues that have led to the interconnection backlog, stakeholders and FERC broadly agree that there is more work to be done, especially around the need for reforms resulting in more substantive investments in grid infrastructure.

Examining the Latest Interconnection Data

This year’s “Queued Up” data release provides the first holistic look at how the system has fared in the immediate aftermath of Order 2023. Most notably, total interconnection queue capacity dropped from 2,600 gigawatts (GW) in 2023 to 2,300 GW in 2024, the first decline in queue size in at least the last decade. This decline was accompanied by a 13% decline in solar and battery storage capacity, which collectively make up 80% of the queue.

On its face, this seems to confirm the effectiveness of FERC Order 2023. However, most of the projects tracked in this data release submitted interconnection applications prior to Order implementation and were not subject to process reforms still underway at many grid operators. Instead, the modest decline in queue capacity was the result of several other factors.

First, some projects that were stuck waiting in the queue for years finally finished the interconnection process and started operating. Both large-scale solar (31 GW) and grid-scale battery storage (11 GW) saw record-amounts of backlogged capacity come online, helping to reduce queue size. At the same time, fewer new projects tried to join the queue in 2024. Due to hesitation around political uncertainty, elevated interest rates, tariffs, and local permitting challenges, 47% less solar and 32% less battery storage capacity entered the queue in 2024 than in 2023. The line got shorter, because fewer people were entering. This same confluence of factors likely helped contribute to a record 112 GW of solar and storage capacity withdrawing from the interconnection queue altogether.

But the most significant reason for declining queue size points back to the impetus driving FERC reforms in the first place. Both CAISO and PJM, two of the largest grid operators, were not accepting new interconnection applications in 2024 as they worked to process the project backlog and implement their own process reforms. Interconnection applications in those territories accounted for nearly 30% of all new queue entrants in 2023, but exactly 0% in 2024.

Jury is Still Out on Existing Interconnection Reform

The interconnection queue reductions observed in 2024 do not provide any meaningful insight into the Order 2023 impacts. It will take several more years for gird operators to process the backlog and adopt new interconnection processes. And while they have promised speedier interconnection times—PJM expects 1 to 2-year wait times—we’ll have to wait to see if this can be achieved.

In the meantime, additional reform is needed. Order 2023 doesn’t adequately address the need for comprehensive regional transmission and grid planning and funding. Some grid operators, including SPP, are taking additional steps to provide for this, our experts at the Solar and Storage Industries Institute (SI2) will show in a forthcoming report. Advocates should continue to push for more comprehensive reforms that address both the cause of the interconnection backlog and the need to enhance the grid to meet the needs of a power-hungry nation.

Regardless of political uncertainty, SI2 remains committed to delivering a more efficient, transparent path for solar and storage projects to connect to the grid.